British Social Documentary Photography and Working Class Identity

Our visual exploration of social housing has a long and rich history in British social documentary photography. We are contextualising our work within this tradition in order to critically evaluate the role of photography in creating and maintaining social identities, and to determine how we can address representations of class in Britain through collaboration and coproduction.

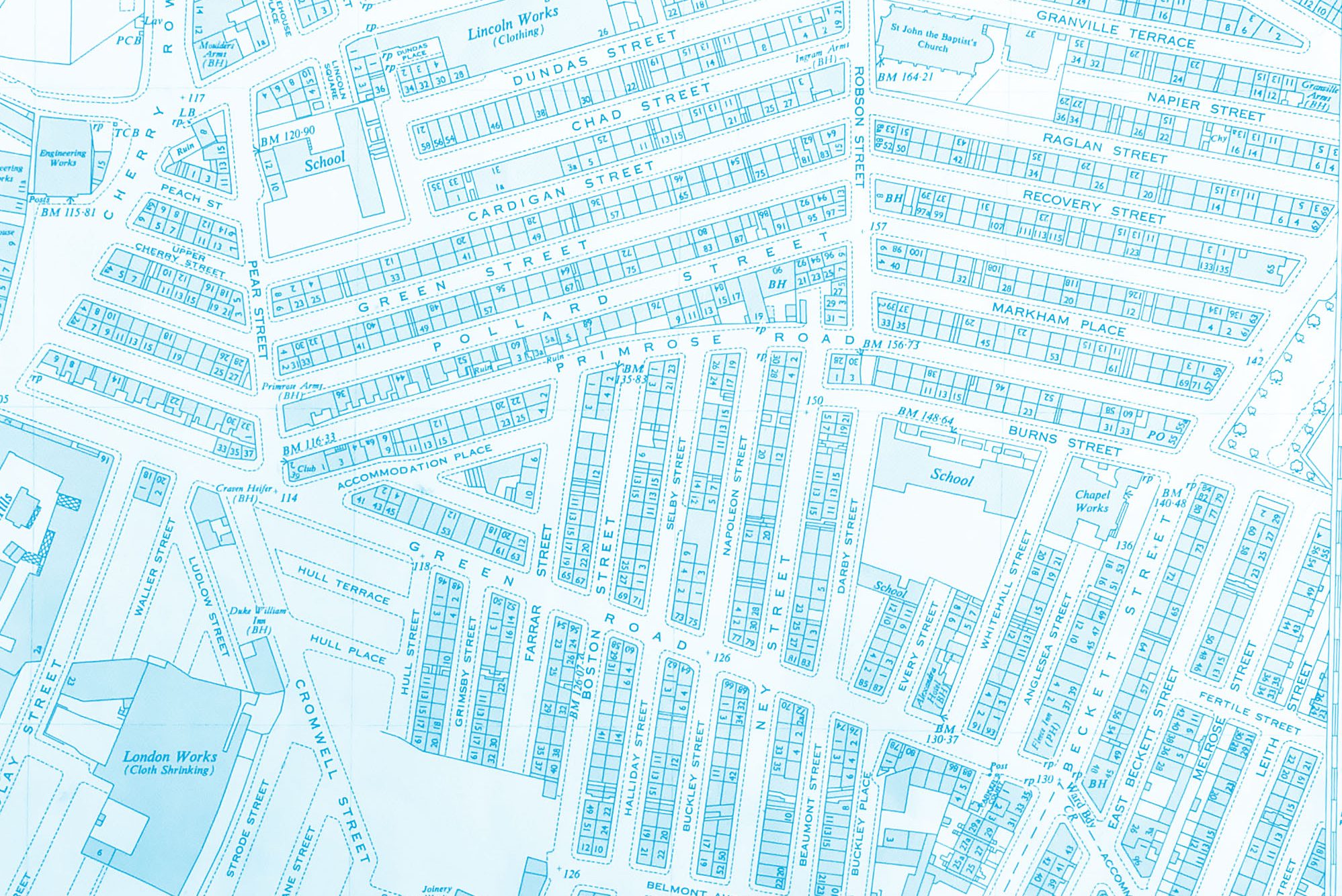

The development of photography in the Victorian era heralded the birth of early social documentary photography, as a tool afforded to the privileged who had the time and money to pursue it. Photography swiftly moved on from images of royalty and the elite, to documentation of the working classes. Through images of the slums and the poor, photography became a tool of institutions of the developing state, as part of the ‘micro physics of power’ practiced through surveillance of the population. This practice stripped the individual down to an object without a voice, one that could be categorised and judged. Social documentary photography set the working class within a social order and became a measure of their worth and ability.

The access of the privileged to these technological processes allowed photographers to render the subjects powerless in their representation. The photographer became the voice of the subject. These early documentary photographs presented the squalor of urban living, but very little of the working life of its subjects. When photographers such as Fox-Talbot presented images of subjects working, they were very often romanticised versions of the working life.

As photography became more affordable to the working classes, they embraced the medium and began to present images of order, work, and neatly presented families against exotic backgrounds, work lockouts and strikes. These images presented a working class identity which differed from their previous objectification. However, the mass adoption of photography, gave rise to a new professional set of codes, to distinguish between a ‘snapshot’ by the ‘ordinary man’, and those who understood the technologies and processes of photography. In this way, social documentary photography allowed the middle classes to reconfirm their identity by establishing what they were not.

The examination of working class culture through photography followed the social ideologies of its time. As such, the photography of the 50s, 60s and 70s highlighted the strength of the working class. However, with the changing politics of the 1980s, images of the working class once again began to echo a Victorian ideology of the undeserving poor. This started the rejection of the identity of a hardworking, respectable and unified working class, to be replaced by an ideology of individual responsibility, as there was now “No such thing as society”.

Social documentary photographers of the time, such as Daniel Meadows, Vanley Burke, Graham Smith, Chris Killip, and Martin Parr were all striving to capture a record of a changing Britain. However, these images no longer portrayed the power of the working classes, but their struggle in a changing political climate. While these later photographers aimed to represent and even celebrate different aspects of working class life, their use of established photographic codes still distanced them from the people who they aimed to represent.

Throughout the 20th century, the representation of the working class in photography has reflected the changing social and political ideologies. Today, in order to address representations of class in Britain through photography, collaboration and coproduction are crucial to challenge the power dynamics that have historically existed in the medium.